Structure Follows Strategy?

Those three simple title words have sparked much debate over many years, as the converse, the idea that strategy follows structure, has been promoted as valid as well. So which is it?

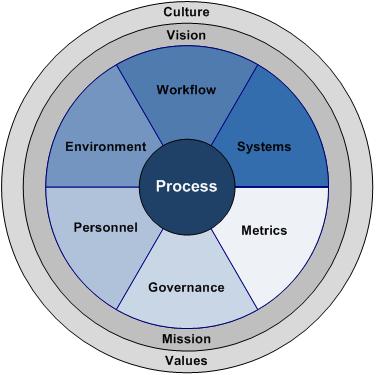

To be sure, the structure of an organization influences the efficiency, effectiveness and agility of its operations. Too many levels to the hierarchy and the good ideas of the folks in the trenches – who can with authority opine on the processes in which they’re engaged – are muffled, if not entirely lost. Too flat an organization, and you have controlled chaos at best, anarchy at worst. (Note that structure is part of the organizational context in which we view processes, a component of “environment”.)

An organization with multiple, highly autonomous functional divisions might have a tough time bringing together multi-discipline project teams for new product launches. On the other hand, an organization that adopts a pure matrix form, where ad hoc teams are assembled for specific projects, might be ill-suited for the demands of highly repetitive processes delivering uniform outputs. The divisionalized structure may have come about as a result of the need to have highly specialized functional units that rarely collaborate (e.g., a property & casualty division, a life and health division, etc.), and best characterizes larger organizations that have, with time, required self-contained divisions to address the unique needs of a certain customer base. The matrix form might come about as a matter of necessity to facilitate growth in a younger, smaller organization, one that is perhaps more focused than its divisionalized counterpart (e.g., personal auto insurance only) and working to create a niche for itself. These cases support the notion that, indeed, structure follows strategy.

But another perspective turns this idea on its head: the notion that strategy follows structure, too, is valid, when you contemplate those organizations that take “inventory” of their available resources and respond by introducing new products or breaking into new markets as a consequence of such availability, and the structure in which they operate. In this instance, strategy follows structure.

So which is correct? What factors influence the “direction” of the title statement?